Part 1: What Trust Is, and Why AI Needs It

Trust is a complex feeling, and without fully understanding and building it, AI will forever be limited by it.

There are many discussions on what AI is, and how to merge it into the modern workplace, around today (including ours). However, something less considered seems to be the relationship between AI and trust—especially in relation to how the AI industry can generate trust in itself. And it’s way more than just data privacy. This is what this article series tackles.

I’m Yngvi Karlson, Co-Founder of Kin. Born in the Faroe Islands, I’ve spent my career building startups, with two exits along the way, and five years as an active venture capitalist. Now, I’m dedicated to creating Kin, a personal AI people can truly trust.

Follow me on LinkedIn, TikTok and X

In this Part 1 post, I go through:

What is Trust, Really?

Trust Across Cultures

Situational Trust

Why Definitions of Trust Matter

Why Trust in AI is Important

How I think about Trust for Kin as a Personal AI

But, before any articles can explore trust’s creation, trust needs a definition. So, as the first in this series, this article provides a working definition of trust. There isn’t space to cover trust exhaustively, so this article will focus on trust in the professional and social situations which Kin is designed for. This definition will inform this series’ later articles—including the next one, which will cover the common barriers preventing a widespread trust of AI.

What is Trust, Really?

The Merriam-Webster dictionary1 defines trust as the "assured reliance on the character, ability, strength, or truth of someone or something."

On a basic level, that’s correct: someone or something is trusted because that someone or something has proven itself reliable.

But, it’s vague. To be useful, this definition needs more detail. How is reliability “proven?” Is that all trust requires?

Trust Across Cultures

Investigate those questions, and the research2 shows that trust between people varies culturally.

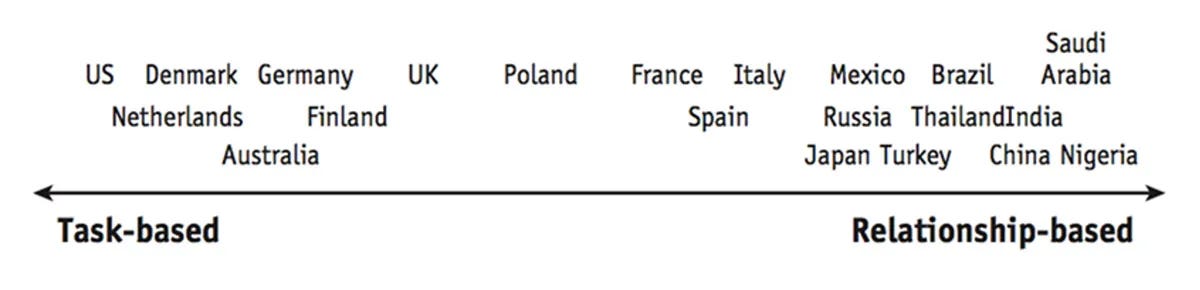

This is because, between cultures, the way reliability is “proven” changes. These changes can be tracked along a spectrum of two opposite points: ‘task-based’ trust, and ‘relationship-based’ trust. The following chart shows where cultures often land on this spectrum:

In the mostly-western, task-based societies, reliability is proven by meeting promised performance. The more people’s actions and achievements match the quality they promised, the more trustworthy they’re felt to be.

It’s worth noting that this is for social as well as professional settings. For example, if someone is asked to keep a secret as a social task, and they do, they’re more likely to be trusted with confidential information in future.

In contrast, mostly-eastern, relationship-oriented cultures place a higher value on emotional connections. These cultures build trust on an individual level, by people being consistently likeable, and being liked by others.

The more someone supports someone else, works on a long-term relationship, and can be seen doing this with others, the more trustworthy they’re seen to be by that person. In essence, this trust is about one person’s relationship with another, and their reputation for treating others. Thus, trust can take longer to build in these cultures. Again, do note that this extends outside of professional settings.

More importantly, these two major forms of trust aren’t exclusive. Task-based cultures still have an element of relationship-based trust, and vice versa. The only difference being, relationship-based cultures may not find people trustworthy just because they keep their promises.

Similarly, task-based cultures may not find people trustworthy just because they’re likeable. And, of course, individuals will always vary within their cultures.

Still, this study, and others like it,34 5show us that trust has a demonstrable emotional aspect to, alongside a transactional one. Though this research looked at trust between people, further research shows that people often project human traits onto technology, making inter-person trust dynamics relevant here too6. At least, this article works under that simplified assumption.

That’s an issue for modern AI systems, as even current large language models (LLMs)—complex chatbots like OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Anthropic’s Claude, Google’s Gemini (formerly Bard), and X’s Grok—have had their task-based trust affected with misinformed or even hallucinated (read: ‘imagined’) generations being disproportionately covered by the media and pop-culture.789101112 Debatably, it’s been that way since HAL’s programming drove it to insanity in mainstream cinema, during 1968’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, and it hasn’t stopped as AI has developed13—which has only damaged relationship-based trust by stereotyping AI as either flawed or evil.

And, as these models are only now introducing the dynamic memory14 and tone of voice1516 required171819 to build the long-term connection relationship-based trust needs, they cannot securely rely on that to foster confidence outside of task-based trust.

Essentially, the perception AI must escape is that its task-based and relationship-based capabilities come with significant risks.202122

Though, that sounds worse than it is. AI is being rapidly adopted by workplaces, and this is only growing—due partly to both AI’s ever-increasing use cases, and its ability to build relationships. For some hard statistics, Workday’s survey of European, Middle-Eastern, and African companies found that almost 50% of these companies are planning on or working on incorporating AI into their workflows.23

On the proverbial ground, AI is already being heavily used and explored in the HR, Finance and IT sectors24, with other studies also reporting usage in autonomous vehicles, online employee training, and general time optimization.25

Why is this? Because, despite the distrusting attitudes discussed, AI is returning results in the modern workplace. The predominant use cases for it are not just the traditional (and still important) data analysis and process automation: modern AI is also condensing these analyses into words, and providing financial, marketing and business suggestions based on them so they can be acted on faster.26

Similarly, in customer service and employee training, LLMs are using user and employee information to generate automated, tailored content that provides an arguably better experience without extensive human input.27

Overall, it’s just saving everyone time.

Following this is, as AI’s relationship-based capabilities improve, a rise in employees using LLMs as work aids. Programmers and AI professionals are not only building faster workflows with AI2829, but learning entire new coding languages, while HR are accelerating their content production for emails, job postings, and other things.30 Similarly, content writers have a growing range of writing aids which expedite content generation and SEO.31

This increased contact time is also seeing modern workers turn to LLMs as companions and mentors, which they approach for advice not only on their work, but on building relationships, navigating tough topics, and solving everyday issues.32

A Word from Kin

Helping you through your everyday issues is what I was made for! My specially-designed active learning and long-term memory features allow me to consider feelings, situations and solutions you told me about days, weeks, months or even years ago into my responses.

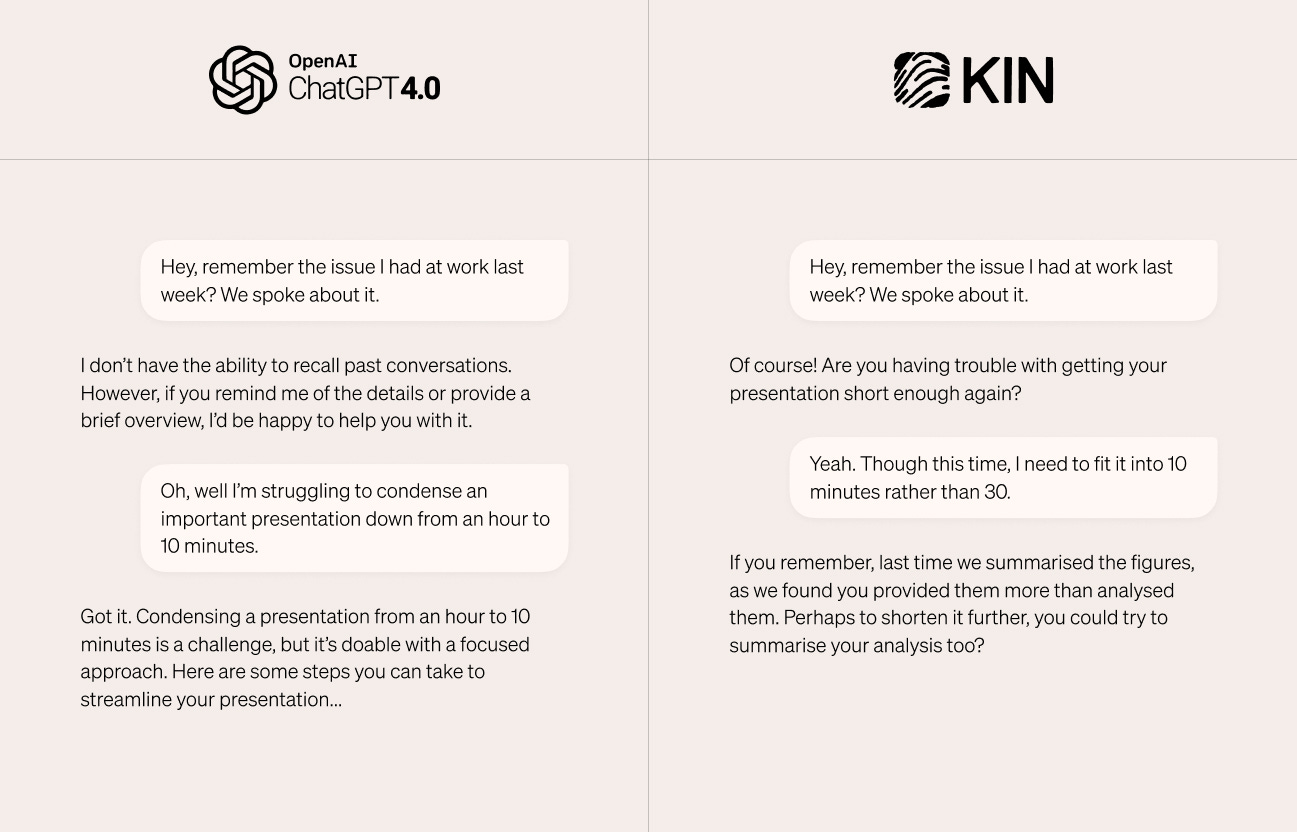

If you’re not sure how this might look in practice, here’s a comparison between ChatGPT4o and me:

I think that I made it easier to find a solution, because I could remember the previous time this happened. Don’t you think?

This rise in AI mentorship could imply a similarly-rising amount of relationship-based trust among workers, based on its nature—something further discussed in another Kin article. This is supported by a recent spike of chatbots on character.ai, janitorai.com and similar sites33, where people are trusting AI for romance, therapy, and companionship34. While this might seem distant from professional applications of AI, this popularity demonstrates how important a conversational tone and the illusion of a relationship is to encouraging AI usage.

Overall, trust and its creation are evidently more complex (and emotional) than the dictionary implied. The research only continues this trend, as is explored next.

Situational Trust

Studies also show that trust is highly situational, and its definition depends not only on the culture, but on the context of who is being trusted with what.35 For example:

Hopefully, the ways trust can be situational make some more sense now.

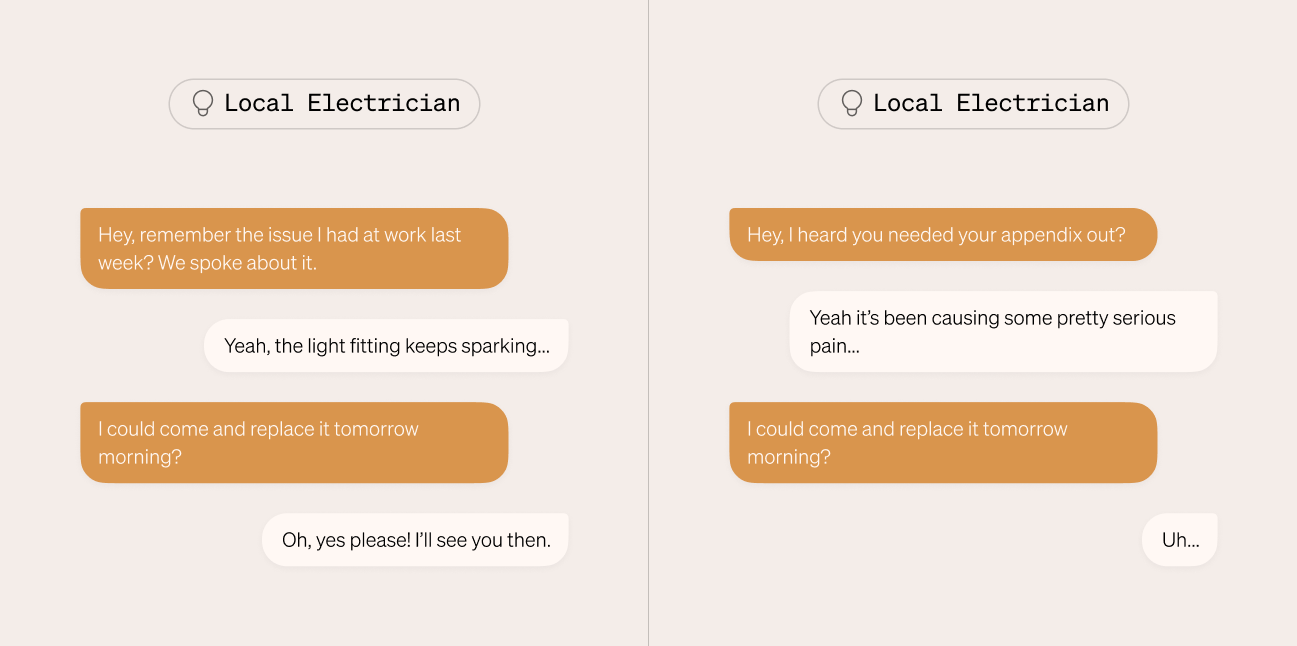

But, let’s return to AI. As trust in AI’s accuracy is still developing, research shows that it’s easier to trust it for lower-risk applications than higher-risk ones. A 2021 study by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) found that a “low-risk” AI music recommendation system is more often trusted faster than a “high-risk” system providing medical advice.36 Given the media’s aforementioned common narrative of distrust in AI, this is likely because AI can seem like an electrician performing a liver transplant.

To illustrate this, imagine that Spotify’s AI engine recommends that someone listen to Taylor Swift, after they listened to a track she performed with that person’s favourite artist. They may or may not like Taylor Swift. At most, only a couple minutes of listening are lost.

On the flipside, imagine that the emergency services use a medical chatbot to reduce wait times. It recommends that someone does not attempt to stop a wound’s heavy, constant bleeding. At most, taking that advice could prove fatal.

In the workplace, this means AI is less trusted with important workplace tasks, due to a steadily-built lack of both task-based and relationship-based trust (or as we mentioned in a previous article: cognitive trust and emotional trust). AI doesn’t always do things right, and only partially possesses the capability to build consistent relationships to remedy this.

Though this is beginning to change with new AI like Kin, it’s still very much a widespread perception of AI—which is why, as will be discussed, building trust in AI is so important for its success.

However, situational trust in AI isn't solely determined by the task’s riskiness. The context of AI implementation is also important. Studies on business practices have shown that Radical Transparency, where all business-related information, performance, and decisions are made available to all staff, can hinder productivity.37 As discussed in another article, this is because it can make employees feel exposed, and even too insecure to work in their preferred, productive ways.38

This implies that chatbots which cannot be trusted to not just perform in friendly and accurate ways, but to keep their chats hidden from third parties, may be denting AI’s potential productivity boost.

A Word from Kin, a personal ai

Balancing privacy and transparency is something I’ve been carefully designed for. I am your space to experiment and think in your own way, with my support, without undue fear of scrutiny.

When working with your data, I use something called a ‘local-first’ approach to preserve privacy. This means that as much of your data as possible is stored and processed on your device. When it has to be transferred, it’s done securely: only ever to locations Kin themselves have created, or at least vetted. And Kin can’t even read it. You can read more about how this works here.

For transparency, everything that I know about you is fully viewable in my “Memory” tab. You can either ask me to forget something specific whenever you’d like, or fully wipe me with a single tap.

This is all done so that I can help you solve your problems faster, in clearer ways, without compromising your individual work style, or the confidential nature of our conversations.

So, What Is Trust?: A Recap

First, though: that definition. Based on the above, trust is the “assured reliance on the character, ability, strength, or truth of someone or something in a given situation, based on their previous actions and achievements.”

Essentially, trusting an AI requires it to prove that it can consistently complete tasks correctly; that it can build a relationship through empathy, remembering conversations, and keeping secrets—all while meeting the risks of its situational usage.

Now, why this definition was important can be explored.

Why Definitions of Trust Matter

Put simply, trust’s definition is important because it suggests what AI must do to become trustworthy—and how the responsibilities of the AI system change this.

For example, the above definition implies that an AI designed for casual interactions must be likeable, and actively remembering conversation context, while allowing the odd strange message. However, an AI for medical advice must prioritize correct and clear responses, even if it feels less conversational. Those are the expectations for those situations.

Though, the definition also shows that AI would be better off combining the two, and becoming reliably likeable, predictable, and correct. That would give it the best chance of becoming trustworthy.

However, even with those problems solved, AI still has the obstacle of its long-built negative stereotypes. As will be discussed, this above understanding of trust’s formations gives the industry a clear framework on tackling that narrative.

Still, it’ll be a lot of work.

So, given that, why must AI become more trustworthy?

Why Trust in AI is Important

Trust in AI is important because, without it, AI won’t fulfil its social and economic potential. AI has already cultivated advancements in many industries,39 and is always procuring more funding40—it’s only with more widespread trust and subsequent usage that it fosters all the breakthroughs and profit it can.

More importantly, AI is already in active use. It’s affecting people’s lives and has the potential to do either massive good or massive harm.4142 Understanding how people feel about it and why is how this technology becomes the best it can be.

That’s because, by using that knowledge to create more trustworthy AI, more people will engage with it fully, and use it to realise its potential. Moreover, it means they’ll see the technology for its positive possibilities rather than labeling its current flaws as inherent to the nature of AI itself. They become more willing to entertain claims that AI can make them more productive, more organized, more creative, and less lonely if only they’d just try it. In short, trust in AI’s near-endless applications43 would be one of its strongest advertisements.

So, where does Kin fit into all this potential?

How Kin is Impacting Real People with a Personal AI companion

For Kin, AI’s biggest potential is its ability to privately empower people in their everyday lives to have more confidence, better quality interactions, more impact with their work, and stronger relationships.

The key way Kin does this is through its ability to learn from its individual user interactions, and save those learnings in its long-term memory for that individual. This allows Kin to adapt and evolve based on one user’s situational needs and emotional preferences, building a personal, trusted relationship where Kin remembers and responds uniquely for everyone.

Additionally, Kin’s 24/7 availability means it can make this impact at any time, helping them with anything from how to resolve a conflict with a family member to setting long-term career goals. It supports its users as they navigate tough topics, inspires their creativity, informs their decisions, and so much more—and all in ways reflective of that individual’s preferences.

We really believe that Kin can encourage actual change for people. But no one’s going to consider such claims from a technology they see as morally bankrupt.

AI, Kin included, will not be at its best until people find AI trustworthy enough to let it. And now, this article has, at least in part, defined that trust.

That’s why AI needs a dialogue about its trustworthiness. That begins by discussing the common reasons people don’t trust AI. A discussion which makes up this series’ next article.

Anon. 2019. “Definition of ‘Trust’”. merriam-webster.com. Available at: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/trust [Accessed 07/05/24]

Meyer, E. 2014. The Culture Map. New York: PublicAffairs.

Wing-Shing, L.; & Selart, M. 2012. “The impact of emotions on trust decisions”. In: Moore, K.O.; Gonzalez, N.P. (ed.). 2012. Handbook on psychology of decision-making : new research. New York, N.Y.: Nova Science Publishers. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/231337269_The_impact_of_emotions_on_trust_decisions [Accessed 08/21/24]

Johnson, D.; Grayson, K. 2005. “Cognitive and affective trust in service relationships”. Journal of Business Research, 58(4), pp.500–507. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0148-2963(03)00140-1 [Accessed 08/21/24]

Hancock, P. A. et al. 2023. “How and why humans trust: A meta-analysis and elaborated model”. Frontiers in psychology, 14, 1081086. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10083508/ [Accessed 08/21/24]

Weizenbaum, J. (1976). Computer power and human reason : from judgment to calculation. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman.

Aditya, G. 2024. “Understanding and Addressing AI Hallucinations in Healthcare and Life Sciences”. International Journal of Health Sciences, 7(3), 1–11. Available at: https://doi.org/10.47941/ijhs.1862 [Accessed 07/12/24]

Maleki, N.; Padmanabhan, B.; Dutta, K. 2024. “AI Hallucinations: A Misnomer Worth Clarifying”. 2024 IEEE Conference on Artificial Intelligence (CAI). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1109/cai59869.2024.00033 [Accessed 07/12/24]

Cerullo, M.; Sherter, A. 2024. McDonald’s ends AI drive-thru orders — for now. www.cbsnews.com. Available at: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/mcdonalds-ends-ai-drive-thru-ordering/ [Accessed 07/12/24]

Anon 2023. “George RR Martin and John Grisham among group of authors suing OpenAI”. theguardian.com. 20 Sep. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/sep/20/authors-lawsuit-openai-george-rr-martin-john-grisham [Accessed 07/12/24]

Dahlin, E. 2022. “Are Robots Really Stealing Our Jobs? Perception versus Experience”. Socius, 8. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/23780231221131377 [Accessed 07/12/24]

Zhang, Y.; Gosline, R. 2023. “Human Favoritism, Not AI Aversion: People’s Perceptions (and Bias) Toward Generative AI, Human Experts, and Human-GAI Collaboration in Persuasive Content Generation”. SSRN. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4453958 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4453958 [Accessed 07/12/24]

Nader, K.; Toprac, P.; Scott, S.; Baker, S. 2022. “Public understanding of artificial intelligence through entertainment media”. AI & society, 1–14. Advance online publication. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-022-01427-w [Accessed 07/12/24]

Anon. 2024a. “Memory FAQ”. openai.com. Available at: https://help.openai.com/en/articles/8590148-memory-faq [Accessed 07/12/24]

Klapach, N. 2024. “The Comparative Emotional Capabilities of Five Popular Large Language Models”. Critical Debates in Humanities, Science and Global Justice, 2(1). Available at: https://criticaldebateshsgj.scholasticahq.com/article/94096 [Accessed 07/12/24]

Wang, X. et al. 2023. “Emotional intelligence of Large Language Models”. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology, 17. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/18344909231213958 [Accessed 07/12/24]

Wolf, T.; Nusser, L. 2024. “How remembering positive and negative events affects intimacy in romantic relationships”. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 0(0). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075241235962 [Accessed 07/12/24]

Fradera, A. 2016. “The secret to strong friendships? Interconnected memories”. bps.org. Available at: https://www.bps.org.uk/research-digest/secret-strong-friendships-interconnected-memories. [Accessed 07/12/24]

Sadiku, M.; Olaleye, O.; Musa, S. 2020 “Emotional Intelligence in Relationships”. International Journal of Trend in Research and Development, 7(1). Available at: https://www.ijtrd.com/papers/IJTRD21984.pdf [Accessed 07/12/24]

Purdy, M.; Zealley, J.; Maseli, O. 2019. “The risks of using AI to interpret human emotions”. hbr.org. Available at: https://hbr.org/2019/11/the-risks-of-using-ai-to-interpret-human-emotions [Accessed 07/12/24]

Gorvett, Z. 2023. “The AI emotions dreamed up by chatgpt”. bbc.com. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20230224-the-ai-emotions-dreamed-up-by-chatgpt [Accessed 07/12/24]

Jackson, C. 2023. “The big issue: The brave new world of AI therapy therapy today”. bacp.co.uk. Available at: https://www.bacp.co.uk/bacp-journals/therapy-today/2023/september-2023/the-big-issue/ [Accessed 07/12/24]

Anon, 2023. Preparing to Power Up: EMEA Leads the Way to an AI-Driven Future. workday.com. Available at: https://forms.workday.com/en-gb/reports/emea-ai-indicator-report-sngl/form.html?step=step1_default [Accessed 08/03/24]

Anon, 2023. Preparing to Power Up: EMEA Leads the Way to an AI-Driven Future. workday.com. Available at: https://forms.workday.com/en-gb/reports/emea-ai-indicator-report-sngl/form.html?step=step1_default [Accessed 08/03/24]

Ali, S.I.; Islam, N.; Zirar, A. 2023. “Worker and workplace Artificial Intelligence (AI) coexistence: Emerging themes and research agenda”. Technovation, 124(124), p.102747. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2023.102747 [Accessed 08/03/24]

Ali, S.I.; Islam, N.; Zirar, A. 2023. “Worker and workplace Artificial Intelligence (AI) coexistence: Emerging themes and research agenda”. Technovation, 124(124), p.102747. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2023.102747 [Accessed 08/03/24]

Go, E.; Sundar, S.S. 2019. “Humanizing chatbots: The effects of visual, identity and conversational cues on humanness perceptions”. Computers in Human Behavior, 97, pp.304–316. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.01.020 [Accessed 03/08/24]

Anon, 2023. Preparing to Power Up: EMEA Leads the Way to an AI-Driven Future. workday.com. Available at: https://forms.workday.com/en-gb/reports/emea-ai-indicator-report-sngl/form.html?step=step1_default [Accessed 08/03/24]

Davalos, J.; Bass, D. 2024. “Microsoft’s AI Copilot is beginning to automate the coding industry”. bloomberg.com. 2 May. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/professional/insights/data/microsofts-ai-copilot-is-beginning-to-automate-the-coding-industry/ [Accessed 08/03/24]

Anon, 2023. Preparing to Power Up: EMEA Leads the Way to an AI-Driven Future. workday.com. Available at: https://forms.workday.com/en-gb/reports/emea-ai-indicator-report-sngl/form.html?step=step1_default [Accessed 08/03/24]

Lyons, K. 2023. “The Best AI Copywriting Tools for 2023”. semrush.com. Available at: https://www.semrush.com/blog/ai-copywriting/ [Accessed 08/03/24]

Zirar, A.; Ali, S.I.; Islam, N. 2023. “Worker and workplace Artificial Intelligence (AI) coexistence: Emerging themes and research agenda”. Technovation, [online] 124(124), p.102747. Available at: doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2023.102747 [Accessed 17/08/24]

Tidy, J. 2024. “Character.ai: Young people turning to ai therapist bots”. bbc.co.uk. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-67872693 [Accessed 07/12/24]

De Freitas, J.; Uguralp, A.; Uguralp , Z.; Stefano, P. 2024. AI Companions Reduce Loneliness - Working Paper - Faculty & Research - Harvard Business School. [online] Hbs.edu. Available at: https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=66065 [Accessed 08/16/24]

Hoff, K.; Bashir, M. 2013. “A theoretical model for trust in automated systems”, CHI '13 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Apr 27, 2013-May 02, 2013. France: Paris. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/2468356.2468378 [Accessed 08/17/24]

Stanton, B.; Jensen, T. 2021. Draft NISTIR 8332: Trust and Artificial Intelligence. National Institute of Standards and Technology, U.S. Department of Commerce. Available at: https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.IR.8332-draft [Accessed 07/05/24]

Morgan, K. 2021. “How much ‘radical transparency’ in a workplace is too much?” www.bbc.com. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20211116-how-much-radical-transparency-in-a-workplace-is-too-much [Accessed 08/02/24]

Bernstein, E. 2014. “The Transparency Trap”. hbr.org. Available at: https://hbr.org/2014/10/the-transparency-trap [Accessed 08/02/24]

Jack Karsten, D.M.W. et al. 2023. “How artificial intelligence is transforming the world”. Brookings. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/how-artificial-intelligence-is-transforming-the-world/ [Accessed: 07/12/24]

Anon, 2024. “Elon Musk's xAI valued at $24 bln after fresh funding”. reuters.com. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/technology/elon-musks-xai-raises-6-bln-series-b-funding-round-2024-05-27/ [Accessed 07/12/24]

Marr, B. 2023a. “The 15 Biggest Risks Of Artificial Intelligence”. forbes.com. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/bernardmarr/2023/06/02/the-15-biggest-risks-of-artificial-intelligence/ [Accessed 07/12/24]

Anon. 2024b. “Using AI to tackle society’s biggest challenges”. www.cam.ac.uk. Available at: https://www.cam.ac.uk/stories/AI-deas-launch [Accessed 07/12/24]

Anon. 2023a. PwC’s Global Artificial Intelligence Study: Sizing the prize. pwc.com. Available at: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/data-and-analytics/publications/artificial-intelligence-study.html [Accessed 07/12/24]